When we talk about access to technology in education, we usually think of iPads and Chromebooks, and the myriad of applications and programs that schools use to engage and support students. But as schools and districts shifted to blended or completely virtual models of teaching and learning in response to COVID-19, a new equity issue emerged that adds yet another barrier for our most vulnerable students: access to reliable and affordable broadband high-speed Internet.

When the pandemic hit this spring, many school districts went to great lengths to secure and distribute laptops and tablets to students who lacked appropriate technology at home. Soon though, school leaders realized that in some areas, even with a device to use, there was little or no Internet service for students to successfully engage in distance learning. Even in areas with sufficient access, the cost to access the Internet was a significant barrier.

The University of Florida’s Lastinger Center for Learning, in their latest brief from their Virtual Listening Tour 2020, went further, saying that “access to broadband, high-speed Internet proved to be the most significant challenge experienced by administrators, educators, students and families in the transition to distance learning.”

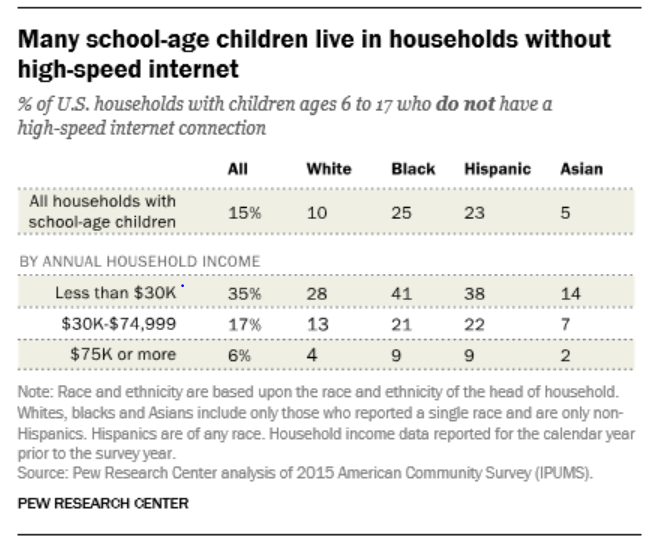

This is especially true in rural communities, which causes concern given that there are 49 small and rural school districts in Florida. The Lastinger Center’s findings, which emerged from interviews and surveys of over 4,000 parents, educators, and families from across the state, largely mirrored those from a 2018 Pew Research Center analysis that showed that 15 percent of U.S. households with school-age children do not have a high-speed Internet connection at home.

The “digital divide” is not a new phenomenon. There has long been a digital and technology resource divide in education that negatively impacts Black, Latinx, and low-income families. But, in the age of COVID-19, the resource and resulting learning gap between students on either side of this divide is more prevalent and more pervasive than ever because schools are relying more on technology, and specifically the Internet, for teaching and learning.

This year, the typical “summer slide” used to describe the slowing of academic progress during the summer months turned into a six-month “COVID slide.” This has compounded already disproportionate learning loss for underserved students who do not have access to supplemental summertime learning opportunities that higher-income students have access to. Coming back to a school setting so dependent on technology and Internet access threatens to widen this gap.

School districts across the state have been working diligently with their communities and the private sector on this newest need so that students can participate fully as digital or blended learners: Pasco County stepped up to cover the cost to reconnect Internet service for families who lost it due to the inability to pay; a number of districts, including Leon, Alachua, and Manatee, partnered with local Internet service providers to mount wi-fi hotspots on school busses that travel to underserved areas; and in Palm Beach County, the district and the county are partnering to install antennas on radio towers on school campuses that will send a wireless Internet signal to underprivileged areas identified by the district.

Longer-term, districts will need to continue to address this persistent connectivity gap, while continuing to support teaching and learning to mitigate the negative effects of the “COVID-slide” on our underserved student groups, such as:

- Building access to technology devices and Internet connectivity into the district’s long-term planning and seeking opportunities that strengthen funding for technology-based infrastructure and support.

- Providing comprehensive, system-wide professional development on virtual teaching and learning for educators, support staff, administrators, and caretakers.

- Planning now to offer strong summer learning programs that engage students in learning through next summer. According to this Rand Corporation essay, the most effective programs “will recruit top teachers, with grade-level experience, and equip them with rigorous academic curriculum. They will operate for five or six weeks of the summer, with three or four hours of academics every day, as well as time for enrichment activities.”

- Identifying your technology needs up front as you plan for your next round of textbook adoptions. As districts launch adoption processes in the context of an urgent need to find new ways to teach students, technological capabilities have become a crucial consideration for new materials. Use this tool from EdReports to articulate the role technology currently plays in instructional materials implementation and the role it needs to play.

Jason Graham is an independent education consultant. He was previously director of teaching and learning at Florida State University Schools.